PART I: AMERICAN ADVENTURES

THE YEARS BEFORE

As a boy in western Massachusetts, I took little note of happenings elsewhere

in the world that would affect my future. The Greenfield Recorder-Gazette,

which brother Bob and I delivered daily, had few headlines about Europe and even

fewer about Asia. American concerns in the '30s were local, centered on making a

living during the Depression, years of widespread unemployment.

I became aware that Hitler was seen as a threat to world peace on a visit to

New Jersey. Newsboys ran through the evening streets waving the Newark papers and

shouting, "Extra! Extra!". (Just like in the movies!, I thought.) Hitler

had become Chancellor, effectively Dictator of Germany. My schoolboy friend Harry

Frank and his family, who had come from Germany, as well as many other Americans,

saw Hitler as the strong leader who would pull Germany out of its slump. Some of

Hitler's early moves seemed reasonable assertions of German nationhood more than

fifteen years after the Great War (as WW I was then called).

Mussolini and his black-shirted Italian fascists were the featured villains of

the time because of their defiance of international law and their brutal conquests

of Ethiopia and Albania. Stalin and his Communist hordes were seen as equal or worse

dangers to the world. And Japan was portrayed as an ruthlessly efficient invader

of China. That this ongoing invasion was made possible by oil and iron supplied

by the U.S. and the European powers was not stressed at the time.

Toward the end of the decade, a bloody Civil War ground down the people of Spain.

Arms came from Mussolini and Hitler to the rebel armies and from Stalin to the government

forces. Depending on the viewpoints of writers, the war was presented to us as a

contest of God-fearing Catholics against atheist Communists or oppressive Fascists

against freedom-loving Republicans.

But then Hitler took over Austria, then part of Czechoslovakia, then all of Czechoslovakia,

then threatened Poland, and then the war came in September 1939. In a few weeks

Poland disappeared into the maws of Hitler's Reich and Stalin's Soviet Union. In

the spring of 1940 Hitler's blitzkrieg made him master of Europe. Great Britain

stood alone, but its air force and navy held off a German invasion. In the summer

of 1941 Hitler turned away from England and sent his armies into Russia. My college

history professor told our class that Russia wouldn't last six weeks.

That same year the U.S. and Britain stopped supplying the Japanese with oil and

iron that supported their invading forces in China. Who knew then that our embargo

would cause the Japanese to attack us in order to grab the oil fields of the East

Indies?

How would the wars abroad affect America's future? From the first, our citizens

were by no means united in supporting Great Britain. "Don't help those damned

imperialists!" And later, many saw the Germans as fighting the good fight against

godless Communism. In the Far East (and how far away it seemed), Japan was seen

by some as merely giving the Chinese a much-needed efficient government. Isolationist

groups, such as the America First Committee, asserted that to keep us neutral we

must give absolutely no help to Britain or China.

I heard arguments for and against our helping Britain when working as an usher

at the Hollywood Bowl. Ushering was an occasional job giving me free entry to concerts

as well as pocket change. My duties were simply to see that the seats were filled

in an orderly manner and that reserved seats were truly reserved.

Charles Lindbergh, a hero to me and many others for his pioneering flights, was

the featured speaker at an American First rally in June 1941. When he came to the

center stage the bowl was filled to overflowing by tens of thousands of concerned

Americans. Lindbergh urged us to avoid European troubles and to build up our own

defenses—popular options in 1941.

Not long before the Hollywood Bowl rally, President Roosevelt, annoyed by propaganda

of American Firsters, had labelled them "Copperheads", a pejorative for

traitors in Civil War days. At this rally a large Italian matron, decorated with

ribbons bearing isolationist slogans and buttons proclaiming support for Mussolini,

spotted me early in the evening. She kept swooping in on me and other ushers trying

to pin on large orange-and-black buttons proclaiming "I AM A COPPERHEAD!"

I resisted her attacks, but some harried co-workers surrendered.

At the Bundles-for-Britain rally, held at the Bowl a few weeks later, no single

speaker had the fame of Lindbergh, nor can I recall the speeches. The rally was

well attended, however, for a large turnout of Hollywood stars was promised. An

area of seating was held for the V.I.P.s of the silver screen. My assignment was

to steer ordinary folks away from that area. My mantra was, "Sorry, these seats

are reserved for motion picture people." After a few hundred or a few thousand

repetitions, I was interrupted by a testy declaration, "But we are in

motion pictures!" This from a handsome Brit escorting a beautiful brunette.

He was Laurence Olivier. She was Vivian Leigh.

For the most part, few thoughts of what the world's troubles meant to our country

rattled around in my adolescent head as I approached maturity after the family moved

to California. A close friend in the Venice High School who did think seriously

about America in a troubled world was Robert Conrad. He was a likeable leader of

our class, a bright student who would have his pick of colleges. When I asked Bob

about his plans, he surprised me by saying that he was not going on to college. "A

war is coming and we have to get ready for it." Bob urged me to go with him

right after graduation to join the Navy. Well, as a youth who once got seasick on

the Hudson River and who lacked Bob's vision, I let him go alone. Now in Hawaii,

you'll find Conrad's name carved into the marble wall of the U.S.S. Arizona Memorial.

In 1940 I went off to college: first Santa Monica Junior College, later the University

of Southern California. Also I had several small jobs, later what I considered a

major one: a blueprint runner at the Douglas Aircraft plant in Santa Monica. I was

on call to deliver prints to departments all over the plant. At that time we were

building twin-engined, two-seat bombers for the British. Our own air force also

ordered many of these light bombers. Designated the B-20, "Boston", it

gave good service early in the war in the South Pacific and later on in Europe.

I went to work at midnight, worked till 7:30, attended classes till 1:00, ate, studied,

slept, then back to work, and often put in two extra shifts on weekends. Of course,

I was pleased with my paycheck (65 cents an hour plus time-and-a-half on Saturdays

and Sundays), but I was also proud to be part of a workforce arming America.

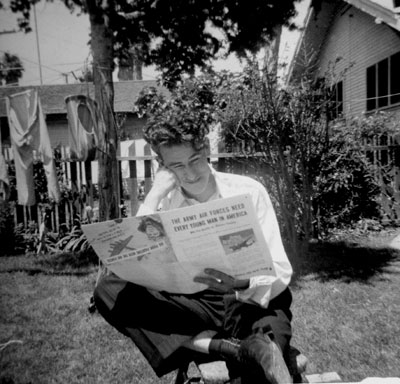

After working the graveyard shift at Douglas Aircraft, followed by classes at Santa

Monica

Junior College, the lure of the Air Force recruitment folder seemed even

more enticing.

I'm perched on a stool in the backyard of 703 Boccaccio Street, Venice, California.

The War Comes to Us

Back to Navigating Through World War II Home Page