Eisenhower's proclamation distributed to all personnel on D-Day, June 6th, 1944

On the morning of June 6th, 1944, the war began for the 493rd Bomb Group. Three squadrons of our silvery new B-24s, for the first time fully loaded with bombs, formed up and flew southeastward to attack an airfield in France. In the excitement of that morning we all cheered the news of the invasion. Everybody on the base seemed stimulated by the release from mere practice. I envied those who flew the D-Day mission, but not too much for our crew was posted to lead the group on the morrow. In the afternoon the high spirits of the morning were dampened when we heard that the group had lost two planes and their crews to a mid-air collision over the Channel.

Eisenhower's proclamation distributed to all personnel on D-Day, June 6th, 1944

If the details of our first lead now elude me, it may be because I dislike remembering failures, let alone embarrassing fiascoes. The assembly of 38 large planes into an organized flight of lead, high, and low squadrons is simple in concept and complex in performance. After takeoff each plane headed toward an assigned radio station, a "buncher" broadcasting a 360-degree signal. Over the station the plane would turn to a specified heading and continue for a specified number of minutes, ascending all the while at a specified rate of climb. Then a reverse course was followed back to the buncher and so on until the altitude specified for the assembly was attained. When we were the first off as group lead, Sergeant Vales would fire red-and-green flares to help others in the flight to recognize their leader. After all the planes had reached altitude and pulled up on us in formation, we'd continue to circle the buncher until it was time to take our appointed place in the Eighth Air Force bomber stream heading for the continent. This assembly was a procedure we had practiced, and we all recognized that it had to be done properly to avoid mid-air collisions.

During my time in England the 493rd lost no planes in assembling, but dawn disasters scarred other groups. Our crew had one near-miss. We were leading an assembly in the pre-dawn darkness, firing off red-and-green flares, when suddenly red and green came rushing toward us—wing lights! Mike and I instinctively ducked as a dark shape shot over us. How common this breath-sucking experience must have been for the R.A.F. night flyers!

The mission of June 7th was to destroy a German airfield near Tours, France. We didn't get there. The Group never fully assembled. Only three or four of us made our way to the departure point over Selsey Bill on the southeastern English coast. As near as I could understand the problem, most of our planes literally got lost in the clouds. This was the first but not the last time that weather was to disrupt operations. Over the English Channel, just about to cross the coast of France, the Command pilot flying with us decided our force was too weak and ordered us to turn back. For this flight our crew received "combat time", a meaningless measure, because for us time was counted in "missions", attacks on enemy targets. For the Tours debacle we rightly received no mission credit. We still had 30 missions to fly.

On the 12th of June we were in the lead again, headed for an attack on an airfield near Beauvais-Tille, France. This time our squadrons were fully formed in a stacks of tight vees. Over the Channel trouble struck us again. Our radio went out. The Command Pilot flying with us couldn't communicate with the Group, so he ordered Woody to abandon his position and place our plane on the wing of the Deputy Lead. But lacking a radio, Woody had no way of telling others what was about to happen. He thrust the plane down in a tight curve and managed to zoom up on the wing of the Deputy. But other planes, puzzled by our unexplained, sudden maneuver, had followed us down and around. As a result, the Group bumbled into French skies with no more order than a flock of crows.

B-24 "Liberator" comes through heavy flak with an engine smoking.

We passed over the invasion beaches. The mass of ships offshore was impressive. As we crossed the front lines the Germans pumped a few shells up at us. We continued on toward the target, but not all was well with the plane. Problems threatened engine failures. Finally, an assessment of grim possibilities led us to leave the formation and head back alone. As a solitary plane deep in Nazi-held territory and still encumbered with a full load of bombs, we were vulnerable to attack by fighters. Woody called on the intercom to Mike and me to quickly pick out a target of opportunity. We soon shouted into the intercom, "We see one! A rail junction just ahead!" Mike pressed his eye to the bombsight. Switches connected. KABOOM!!! As we passed beyond the target Mike and I realized we'd just wiped out the crossing of two dirt roads...

Three days after spooking some French cows, we saw Paris for the first time on an attack on a nearby airfield at Toussou-Le-Noble. The field was defended by several guns, but only later did we realize that the anti-aircraft fire was light.

We learned what intense flak was on our third outing. On the morning of June 20th when the curtain over the mission map was pulled back in the briefing room, we knew we were to fly into danger. The red tape stretched across the North Sea and the Netherlands into northwest Germany.

The prescribed route into Deutschland was one we were to know well in the months to come. We made landfall over Egmond aan Zee, a village on the Dutch coast, thereby avoiding Nazi guns at the town of Alkmaar just to the north. Then we crossed the Zuider Zee along the south edge of the Northeast Polder. The polder was one of several large, diked mudflats, which the Netherlanders were reclaiming from the sea. The polders wouldn't support heavy guns. If the route was navigated carefully, we had 20 minutes or so without a puff of flak. [It was the Zuiderzee in my service days but it's now the IJsselmeer. The Dutch built a great dam across what had been a brackish bay opening to the North Sea. The present-day IJsselmeer is a fresh-water lake. The polders, the large areas of dike-protected mudflats that bordered the bay, now support busy towns and thriving farms.]

Once into Germany we dodged cities and factories known to be surrounded by AA batteries. This knowledge came largely from bitter experience of flyers on earlier missions. Our target was an oil refinery at Misburg near Hannover. The Germans knew what we were after, because airforces out of Britain and Italy had begun to concentrate on the Nazi fuel supplies. The Germans put up a box barrage filling the part of the sky we had to fly through on the bomb run. We bounced through the box of shrapnel. Our bombs fell on the aiming point. Raging fires in the refinery sent black smoke boiling up to 20,000 feet as we pulled away. I thought we'd completely destroyed the facility, but six months later the 493rd went back and wiped it out again.

In our B24s we made three other attacks on oil targets: on refineries near Brussels, Belgium, and at Hemmingstedt near Husum, Germany, on the Northfriesland coast, and on a fuel storage area near St. Florentine in central France. They were all well armed with flak batteries.

We added Jouvaincourt, France, to the Luftwaffe airfields we plowed under. Only one gun defended that field, but gunner Hans and his Fliegerabwehrkanone had plenty of practice that day. Our assigned approach put us into a headwind that anchored us in the air. As we gradually worked our way toward the target, Hans von Below kept pot-shotting at us for 20 minutes or more. When we could see the red flash in the middle of the columnar puff of black, we knew he was zeroing in. Somehow he kept missing, and after "Bombs away!" we made for England. We came down to a lower altitude and were cruising westward over French farmlands when suddenly a 20-mm battery opened up on us. Luckily, we were still high enough to be out of their range. The shells fell far short, like so many tennis balls curving over below us. We came in low to England over Clacton-on-Sea when unexpectedly more flak burst around us. Someone had the wrong IFF code (Identification-Friend-or-Foe radio signal). In spite of these several hazards our plane received no serious damage that day.

A 493rd B-24 drops its load on an area near St. Lo, France, July 1944.

On the 24th and 25th of July we took part in the intense carpet bombing of German positions near St. Lo. As we readied for our attack the group ahead of us bore the brunt of anti-aircraft fire. One of their B-24s slipped off to the right and another fell off to the left. I quit watching them when it was our turn over the lines. The exploding bombs of the first group knocked out the flak guns, but also obscured the front lines marked by smoke pots. Our load fell beyond the area struck by the first group, but some American bombs fell among our own GIs. Nevertheless, the bombardments aided the subsequent breakout by our troops on the ground. [My brother Bob, a combat engineer who splashed ashore on D-day and was in the fight around St. Lo, often twitted me about dropping high explosives all around him in July. I assured him that Eighth Air Force bombing was perhaps 90 percent accurate on almost 50 percent of our missions.]

On August 14th our plane led the whole Third Division of the Eighth Air Force out of England. Our assigned target was a railyard at Angouleme in southwestern France. The roundhouse that shuffled the locomotives had to be destroyed. We flew at the relatively low level of 15,000 feet to give Mike a better aim. The purpose of destroying the railhead was to hinder German troops in southwestern France from moving against our army in Normandy or the force that was soon to land in southern France. Lead Bombardier Wright was commended for accuracy on this mission. The exploding bomb string marched right through the critical roundhouse as intended. Unfortunately, the first impacts were along the main street opposite the cathedral.

CRASH ALERT!

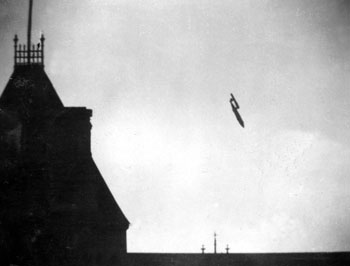

This photo of a plunging V-1, said to have been taken in London, was given me by the base photographer. Presumably it was a U.S. Army photo, but it appeared widely in the public press. In London I was never close to the impact of a buzz bomb, and yet I once felt the concussion wave of a bomb that hit far away.

Buzz Bombs and Rockets

In the summer of '44 the Germans began attacking London with pilotless bombs, "V-1s" or "revenge weapons" in Nazi parlance. Those on the receiving end called them "buzz bombs" or "doodlebugs" with varied adjectival expletives.

You could hear the steady put-put-put-put of a V-1 from a long way off. As the steady beat grew louder, you anxiously waited for the weapon to pass over. If the motor cut out, you sought cover. The bomb was falling. A tremendous blast was coming. Of course, the buzz bombs had little military value, but they could scarcely miss such an enormous target as London and its suburbs. The attacks drove families back into sleeping in the Underground as during the 1940-41 blitz bombing by the Luftwaffe. All of us soldiers on leave in the city were reminded of the realities of war when we heard the popping jets of an oncoming V-1 or when we had to make our way around sleeping bodies on the subway platforms.

Later in the year after our troops had retaken France, the Nazis began launching night attacks from the Netherlands so that the V-1s passed over East Anglia. From Debach we could hear the boom! boom! of British anti-aircraft guns near the coast. They knocked many V-1s out of the sky. One memorable night a buzz bomb stopped its deep-throated sputter near our airfield. Everybody and everything on the base stopped. In the sudden silence I could hear crickets chirping. We flattened out on the cement floor of our hut, waiting for the explosion....but it was a dud. We may owe much to a slave laborer who sabotaged the fuse. The next day Mike dug himself a commodious slit trench behind our hut. No doubt, if more buzz bombs fell near Debach, we'd all have piled on top of him.

Later in the year after our troops had retaken France, the Nazis began launching night attacks from the Netherlands so that the V-1s passed over East Anglia. From Debach we could hear the boom! boom! of British anti-aircraft guns near the coast. They knocked many V-1s out of the sky. One memorable night a buzz bomb stopped its deep-throated sputter near our airfield. Everybody and everything on the base stopped. In the sudden silence I could hear crickets chirping. We flattened out on the cement floor of our hut, waiting for the explosion....but it was a dud. We may owe much to a slave laborer who sabotaged the fuse. The next day Mike dug himself a commodious slit trench behind our hut. No doubt, if more buzz bombs fell near Debach, we'd all have piled on top of him.

In our B-24s we took out a V-1 factory in Russelsheim in southwestern Germany and attacked three launching sites in France. The launch sites were well camouflaged. The targets, as given to us, were merely a mark on a corner of a field or the middle of a grove of trees. These sites were called "no-balls", perhaps because they lacked machismo. They were not strongly defended. Such easy missions were considered "milk runs", though a single unlucky burst of flak might destroy a plane. Even so, later in the year I wished we had been assigned more such missions.

The Eighth Air Force didn't attack the V-2s. These were the large, liquid-fueled rockets that arched unseen and unheard across the North Sea to explode in London with devastating effect. The gargantuan missiles were launched from easily moved platforms, which we could not target. The R.A.F. pockmarked the V-2 research station at Peenemunde in northern Germany, but the factories making the weapon were safely hidden underground.

Our group, however, had one strange experience with a V-2. On our way to Germany, five miles above the land, I looked down to check our position as we crossed the Dutch coast. A long dark object was wobbling up toward us. It reminded me of a telephone pole. Before I could suppress this ridiculous thought, the shape shot by us. Had they fired the giant rocket at us hoping to destroy all thirty-eight planes in one blow? Or was it a mere coincidence that we passed over as they sent the monster toward London?

Transition Time

In mid-August we learned that the group was going to lose its B-24s and be re-equipped with B-17s. Commanders of the Third Air Division found it difficult to co-ordinate an attack by a mixed armada of 24s and 17s. Standard procedure called for the 24s to fly about 10 miles an hour faster and a few thousand feet lower than the 17s. As for me, I appreciated the extra speed the 24 carried us through the flak. Flyers of the 17s claimed it was better to be higher above the flak batteries.

Our B-24J had served us well, bringing us back from ten missions into France, one into Belgium, and three into Germany. I'd become used to seeing the slight flutter at the tips of the long silver wings. I was comfortable with my station and familiar with other positions in the plane. Woody had let me sit in the nose turret on a few landings, a thrilling ride down to the ground. He also once let me handle the controls of the plane for a minute or two. Previously I'd piloted a nimble Piper Cub. I didn't anticipate the slow response of a big airplane to the controls. Consequently, when I was in the co-pilot seat our plane bobbed through the English sky like a giant porpoise.

In mid-July I exchanged my brass bars, gained in Hondo, for the silver bars of a First Lieutenant. Six months earlier I'd been sweating out navigation school. At this rate of promotion in a couple of years they'd make me a General. July also was the month in which Colonel Helton pinned the Air Medal on my uniform. All crew members who had completed five missions were in line for this medal. We realized that the honor was more for the luck of surviving than for "meritorious achievement" with attendant "courage, coolness, and skill". By the end of our B-24 days the medal was re-awarded as an Oak Leaf Cluster on the blue-and-orange ribbon. More little brass clusters remained to be won before the last landing on the Debach runway.

Life on the Base

Our English quarters were Nissen huts made up of curved sections of corrugated steel. They could be quickly put up as half-round sheds and closed by wood at each end. In the middle of the hut was a small, coke-burning iron stove. At times it seemed to absorb rather than radiate heat. Eight officers were crowded into the one room. Besides Woody, Rawson, Wright, and me, later joined by Frank Littleton, the crew of David "Doc" Conger (pilot), Elwood "Sammy" Samson (navigator), and Howard Ropa (bombardier) bunked down in this hut. Toilet and bathing facilities were in another Nissen building, which in a British euphemism was called the "ablutions room".

I posted this page above my bunk on the wall of the Nissen hut in Debach.

My idea of humor at the time.

We spent much of our time in the hut, especially on the all too frequent days of bad weather. As the chilling, damp English winter closed in on Debach, we tended to huddle around the comfort of our little stove. Considerable effort was given to adding to our meager allotment of fuel. We cadged large wooden bomb boxes for kindling and storage. We also filched lumps of coke from the squadron pile until Major Hale placed a 24-hour sentry to guard it.

Because crews were constantly on call, we were generally restricted to the base until the day's flying had been done. Several diversions on the base were open to us. No doubt, the most widely enjoyed was the theater where current Hollywood movies were shown. The Officers' Club served British ale and occasionally beer and whiskey. A seeker could always find partners for a card game or a roll of dice.

Women were seldom seen within the perimeter of Station 152. Exceptions were the uniformed Red Cross volunteers who often drove up in their truck to serve us much appreciated coffee and donuts. Base parties were arranged now and then, celebrating this or that, such as the completion of the Group's 100th mission. Women from nearby areas were invited. (Among them was an attractive blonde nymph, who, our squadron doctor warned us, was "a potful of pus".) Although I and other clodhoppers didn't join in the dancing, we enjoyed the diversions.

One of the nicer parties of the 493rd was given to local children in the Christmas season. Among the gifts from America were oranges. Because of the war the children had never seen such fruit and were puzzled as to how to eat them.

One of my rarer amusements was the Group bombardier trainer. To maintain his proficiency Mike had to log prescribed hours in this tower. The building housed a Norden bombsight mounted on a balcony. An overhead projector cast moving photo images of targets on the floor below. Mike went through the procedures of aiming and triggering. The machine stopped and showed by a dot of light where his bombs would have hit. For Mike, handling this machine was just another tedious bit of training. When I joined him and worked it, I found it fun. In this building I got to "bomb" Berlin without leaving the base.

Frank Littleton, Hut G resident, with his cigar and bicycle.

Frank Littleton, Hut G resident, with his cigar and bicycle.

Much of our time was spent in the Nissen hut, more as winter came on. Here we passed hours in talk, speculating mostly about war and women. Here we wrote V-mail letters home and read and re-read those we received. Here we watched in amused amazement as Dave Conger emptied a clip out of his pistol at the hut rat, who, though somewhat deafened by the experience, often came back to study us. Here sometimes one or more of us might seek to withdraw from the camaraderie to be alone with our private thoughts. My favorite retreat to a different reality during days in the Debach hut was reading Parkman's The Oregon Trail. Although the part of America and the times he dealt with were as foreign to me as the Antarctic and the Middle Ages, his story seemed a tie to home. I read the book cover-to-cover many times and long treasured that battered copy.

Into German Skies in a "Flying Fortress"—the B-17

Back to Navigating Through World War II Home Page