About to board my aerial steed

About to board my aerial steed In February 1945 I thought the war would go on for a long time. I recalled that back in 1942 LIFE Magazine had predicted that the fall of Singapore meant that the war would last another 10 years. In December 1944 the Stars and Stripes, a widely distributed newspaper published for the armed forces, carried this headline: U.S NAVY ESTIMATES THAT IT WILL TAKE FIVE MORE YEARS OF FIGHTING IN THE PACIFIC. The story was based on a statement from a regional director of the War Production Board, who foresaw a great need for more armaments. In the Philippines, MacArthur's forces were slowly advancing against bitterly resisting Japanese. The marines had just begun the hell fight of Iwo Jima against 25,000 suicidal Japanese. A few months later, in Okinawa came some of the nastiest fighting of the war against a kamikaze enemy who preferred self-destruction to surrender. Meanwhile in early '45, the advance into Germany continued as a bloody grind. The Eighth Air Force was still fighting the weather and the Luftwaffe. And if the war in Europe ended soon, I thought many airmen would join me in retraining for the Pacific battles yet to come.

Texas, Again

Orders were cut in Santa Ana sending me in March once again to Texas, to San Marcos about 50 miles north of San Antonio. San Marcos was a parking place for officers awaiting assignment. I kept up my navigator's trade in flights in a small twin-engined plane used mainly to train pilots.

In San Marcos I was barracked with a lieutenant just back from the Pacific. He was a high-spirited Texan, proud of his Lone Star State accent and knowing the customs of the country. What's more he was privileged to have a car when few lieutenants did. He often gave me a ride into town or all the way to San Antonio. One day, as I climbed into his convertible, I asked, "How do you get gas in this time of strict gas rationing?" "Watch!", he said. We zipped around the base to the flight line. He slammed to a stop behind some parked planes and walked over to a small store of gasoline cans. He hefted one and nonchalantly emptied it into his car's tank. Though I could admire his cool daring (a man to fight a war!), I knew that the U.S. Army would regard his act as blatant larceny and myself as an accessory in the crime. Thereafter, to avoid a court-martial I avoided him.

After a month in San Marcos I transferred south to the base outside San Antonio. This large base was in part a pre-flight school. Here I repeated the same aptitude tests and many of the same short courses that I'd taken almost two years ago. The results were about the same as before, good but not exceptional.

On the first of May I put my signature on a form applying for pilot training "...recognizing that upon completion ... I may be assigned to an additional tour of duty overseas." As long as the war went on, I'd be in it.

V-E Day

On May 7th, 1945 the war in Europe ended. How did I celebrate VE Day? I didn't. No one on the San Antonio base did. The commander locked the gates and closed the officer's club and all facilities except the mess hall at specified hours. All the air cadets in training at the pre-flight school learned that they were to be transferred to the infantry. A sullen gloom enveloped the base. One disgruntled cadet guard momentarily sighted his rifle at me. That day, for him, all AAF brass down to lieutenants were the enemy.

Lancaster, California

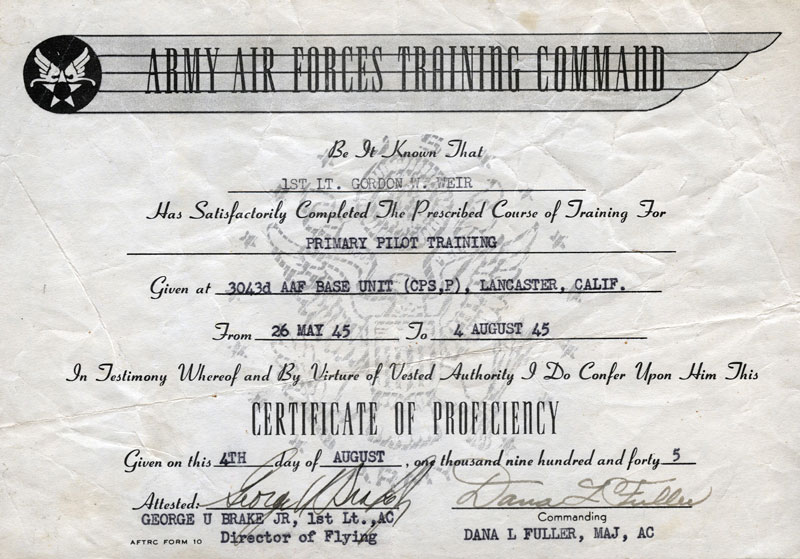

The following week I reported in at my new station, the Primary Flying School at Lancaster, California. The field was on the edge of the Mojave Desert. The well-known Edwards Air Base, the Air Force's testing ground, was nearby. Los Angeles was only 60 miles away, little more than an hour's zip around the San Gabriel Mountains and over the Santa Monicas. Fellow trainees who had cars carried me to my Venice home on weekends.

Dad

Dad was still weak as he had been during my February visit but he was in good spirits. Thus, I was shocked and saddened when his heart gave out suddenly in late May. [How many words I'd left unsaid to him!] Mother was comforted that one of her sons in the services could stand by her at the funeral.

Earlier that month Dad had sent me a letter with news of the family written in his fine hand. As a veteran of the Spanish-American War and having had three brothers in World War I, he added this advice:

"The Army life after some time, will get you in a rut, and unless you would make it your career, I would say to you, get out of it as soon as your country does not require your services. The opportunity to finish your education is still open, and to put in any more great length of time in the service might make it much harder for you to regain your mental balance again."

"Mental balance"?—perhaps my father had perceived that which I thought well hidden. Once initiated into combat, I tried to maintain, outwardly at least, a stoic demeanor proper to a soldier. But I could not control the subconscious mind. Not long after the 493rd began sending its bombers over Europe, I watched one of our B-24s come lumbering over Debach with two engines feathered. As the plane struggled back toward the runway, it stalled and fell. Trees and buildings obscured the plane at the moment of impact, but the meaning of the pillar of oily smoke in the middle distance was plain. Ten men died.

Pilot Training

At the Primary Flying School outside Lancaster, California I met one of the Loves of My Life—the Stearman PT-17. The AAF gave it the official nickname of "Kaydet", but no one called this yellow- and-blue, fabric-covered biplane anything but the "Stearman" or the "Pee Tee Seventeen". This training plane was much like the World War I Spads and Albatrosses that as a boy I'd whittled out of balsawood. Alone in this two-seater you could feel yourself to be like the American ace, Eddie Rickenbacker, or the Red Baron himself.

. About to board my aerial steed

About to board my aerial steed

Our instructors showed us how to move the ailerons on the wings, the elevators on the tail, and the rudder on the tailfin. Using these controls you could move take your plane up, down, and around. The instrument panel was simple: oil-pressure and rpm gauges on the 220 HP engine, a bank-and-turn indicator, an air-speed dial, and an altimeter. In the PT-17, however, you flew mostly the old fashioned way, "by the seat of your pants", judging everything by eye from your cockpit.

For a few days we practiced take offs and landings and made short flights over the surrounding Mojave Desert. On June 16th, I soloed. As I pushed the throttle forward, I wasn't sure I was ready for this moment of truth. All went well on the takeoff and the turn into the traffic pattern. Other Stearmans were ahead of me, when suddenly my plane lurched and was slow to respond to the controls. With puzzled anxiety I circled the field again. Then I shamefacedly realized that I'd merely bumped into turbulent air from propwash of the planes ahead or a bubble of air rising from the heating desert.

Instructors showed us how to do simple acrobatics and then sent us up alone to practice them. The chandelle was a shallow dive building up speed for a zooming turn. Loops were begun the same way but you pulled the plane up and over. Snap rolls were pivoting the plane quickly while holding it level on a horizontal axis. Slow rolls were virtually the same maneuver done slowly. This roll required fine coordination, because as you slowly pivoted the plane through the upside-down position the control surfaces reversed functions. This maneuver was one I never did well twice in a row. In my final test in the air the nose slipped down during the rollover. I knew it was sloppily done. The Army check pilot at the end of the ride, climbed out of the cockpit, looked at me and said gruffly (and perhaps with a bit of humor), "You passed, but your slow rolls lacked perfection."

The world was protected from us fledgling pilots by a no-fly zone hash-marked in red on all air charts. Other airplanes were to keep out of our playground. Even so, we surveyed our area before beginning acrobatics. Tempting Icarus's fate, I'd push my Stearman thousands of feet above the desert floor, then kick the plane into a spin. In a spin the plane gyrates downward nearly flat and does not respond to the controls on the wings. The pilot is helpless unless he dumps the nose down to get more speed before pulling out of the spin. It was a maneuver worth practicing to know how to get out of quickly. One morning I was spiraling downward when I became conscious of another fast-moving shape. I dove, leveled off, and looked up. I'd just missed colliding with a twin-engined airliner!

A first lieutenant lacked the anxieties of an aviation cadet. My civilian instructors may have been less impressed by my piloting skills than by my uniform. At that time, over the left pocket of my jacket were the European campaign ribbon studded with battle stars, the air medal with oak leaf clusters, and the Distinguished Flying Cross. For me pilot training was less stressful than navigator school. If I failed, "washed out" by a check pilot, I'd still sport my navigator wings and first-lieutenant bars. So though Primary required serious application, I could relax and enjoy flying the PT-17 for the fun that it was.

The Stearman was tricky to land. Especially was this so in a wind, and the Mojave desert bred sudden, unexpected gusts across the Lancaster field. The plane was balanced on a narrow landing gear so that it was easily tipped. You had to keep "flying" the plane as it rolled along the ground. If a tilted wing touched the ground, the plane would tend to spin around the dragging tip in a "ground loop". At the end of Primary I was the proud recipient of a certificate honoring my flying as free of ground loops. However, my roommate had a good laugh on me and on the system. He was awarded the same certificate, even though he'd scraped the fabric off the wingtips of five airplanes.

F.P. Quileilak; H.S. Broemelkamp; John C. Weir (!) Instructor; Walt Foster; G.W. Weir

Back to Navigating Through World War II Home Page