|

CHINA THOUGHTS

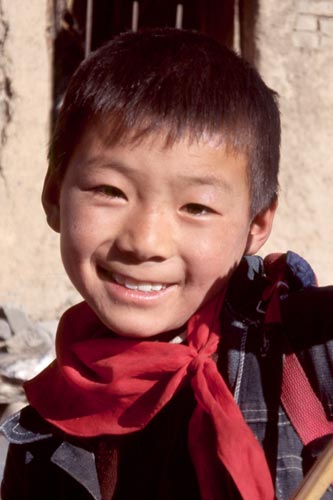

Happiness

Although most Chinese put in a long, hard day's work

for low wages and have to put up with all kinds of inconveniences, somehow

they nearly always manage to be cheerful. This is one of the delights of

traveling in China.

Health

The Chinese definitely need to improve their living

habits—smoking, spitting, and industrial pollution here are among

the worst in the world. On the other hand, restaurant people are good about "boiling

it, cooking it, peeling it, or forgetting it." I've always been able

to get boiled water at hotels and restaurants.

Bill's Health

I mentioned that "Bessie Too the Bicycle"

has held well up for the entire trip without a visit to a bike shop. Bill

did even better over the four months, without getting sick or suffering

an injury despite some long, tough days. That's partly because cycling is

such and enjoyable sport that one tends to be happier and physically stronger.

Wealth

If you're wondering why petrol prices are so high, one

reason is that wealthy Chinese love to drive big SUVs. I've seen a few Hummers,

but Mitsubishis, Toyotas, and Jeep Cherokees are the most popular. While

some Chinese do very well financially, the majority do not. Unemployment

remains one of the government's biggest challenges.

Safety

Chinese drivers are well accustomed to dodging slower-moving

objects on the road and have a marvelous ability to survive near misses.

I use a rear-view mirror to keep an eye on what's going on while I'm cycling.

Nearly all Chinese are honest, with bill padding at restaurants and hotels

the main hazard. Theft is said to be a danger at bus and train stations

and on crowded buses and trains, places I easily avoid. Cyclists have lost

their money belts to thieves elsewhere, however, so I try to be very careful.

The Chinese Government

You have to give credit to the leaders

of this police state for successfully guiding their huge population on an

unprecedented growth rate for the past two decades. The government has also

managed to hold the country together despite the aspirations of some minority

groups, especially in the west, to break away. The Chinese people really

seem to enjoy their current economic freedoms, though democracy does not

seem to be on the horizon. No Chinese on the mainland have ever told me

that they desire a democracy. The problem with China's one-party system

is that it lacks checks and balances; corruption at high levels is said

to be a major problem in the country's development. The government also

HATES criticism—most citizens know better than to risk the wrath of

officials! The US government's latest human rights report about China was

not appreciated, and the Chinese responded with a scathing report of their

own about crime and Iraq prison abuses of the United States.

Chairman Mao Zedong

The "Great Helmsman" still appears

on posters, currency, and as massive statues. The Chinese remember him as

a resourceful leader against the Japanese during WWII and as one of the

founders of the Peoples Republic of China. While he helped lift the country

out of the economic depression caused by WWII and civil wars, his policies

also led to famines, invasion of Tibet, and the terrible persecutions and

destruction of the misnamed Cultural Revolution (1966-70). Today, Mao's

communist policies have fallen by the wayside, but he remains a folk figure.

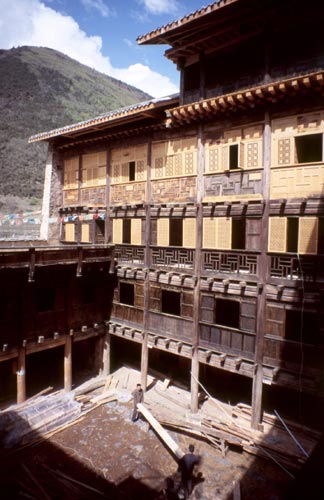

China Transformations

This is my fourth visit to mainland China,

with the first one back in 1982. That trip was totally unplanned. When China

opened to tourism, only groups could come and each member had to pay about

$100 per day—way, way over my budget. But on a cycling trip through

East Asia in early 1982, I stopped off for a brief visit to Hong Kong and

found my hostel flooded with travelers who had just come back from mainland

China. The country had just opened to low-cost independent travel! I stored

my bicycle and took off on a six-week grand tour of China. Travel remained

highly restricted—if a place wasn't on my permit, I couldn't go there—so

cycling touring didn't seem to be an option. There were no guidebooks at

the time, so I relied on other traveler's notes about what to see and where

to stay—it was a great adventure. I found city streets streaming with

bicycles as nobody had private cars then. Shops were filled with drab merchandise

that nobody especially wanted, but tourists and well-connected Chinese could

use black-market money to visit the Friendship Stores, which had the good

stuff. A few daring young women wore Western fashions, but most everyone

else only had dark, dull, monochromatic clothing of the Communist era. I

was back in the steam age—the sound of steam whistles was common and

I often rode on steam trains, even on the main lines. Shanghai, especially,

looked like a city in a 1930s black-and-white movie; the old architecture

had hardly changed since the Communists took power.

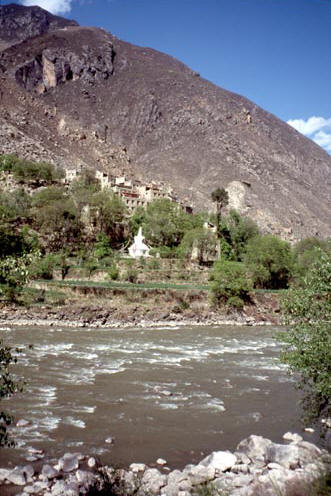

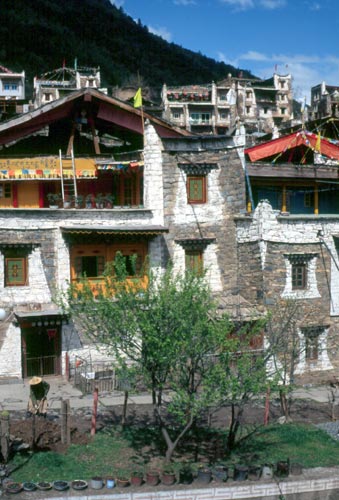

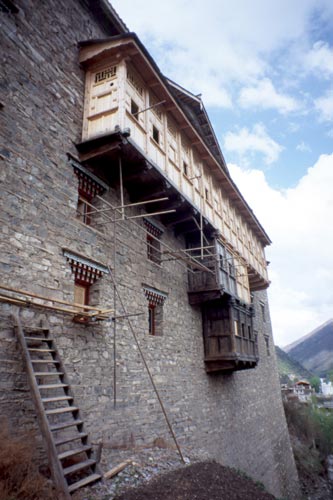

Tibet

My descriptions of traveling in Tibetan lands of northern

Yunnan and western Sichuan may have been a bit confusing because these are

no longer part of Tibet. When China occupied Tibet, large chunks were lopped

off into Yunnan to the southeast, Sichuan to the east, and Qinghai to the

north. The remaining parts of Tibet became the Tibetan Autonomous Region

(T.A.R.) even though the Tibetans have no autonomy! The Tibetans I met in

Yunnan and Sichuan seemed to be doing well. The government also seems to

be allowing a fair amount of religious freedom.

Newspapers

I've never been to a country with so few of these.

Only the cities have newspapers, and only tourist centers have anything

in English. Of course, the papers that do exist only print what the government

approves. Most Chinese prefer to get their news and entertainment from television.

Internet Cafes

One frequently hears of government crackdowns

on these based on moral grounds. Here I'm 100% with the authorities. Most

Internet Cafes in China are dark, dismal, filthy, smoky dives that desperately

need either closing down or cleaning up. The Chinese are at their worst

here; most users come to play games or watch movies. The computers are aging

machines without software updates. At least they are cheap and often have

useable Internet access. I try to find Internet computers elsewhere, such

as in hotel business centers or Westerner-friendly guesthouses.

The Great Firewall of China

I've never found a computer

with high-speed Internet in China. Part of the problem may be the

government monitoring of e-mail and websites that probably takes place.

Some sites are temporarily or permanently blocked. The BBC's site has

been blocked at times in the past, for example, though I've usually been

able to access it.

Hotels

My guidebook tells a humorous story of a "typical"

Chinese hotel where the Western guest encounters one problem after another;

when his head finally hits the pillow, loud karaoke downstairs starts up.

Hotel descriptions in the guidebook usually feature dormitories as the top

budget option. But hotels have improved greatly in recent years. The biggest

improvement has been the dropping of "foreigners prices" that

once doubled or tripled a room's cost; this was purely racist as hotels

gave overseas Chinese the regular price. Another government trick to rip

off Westerners was the police policy of only permitting the more expensive

hotels in town to accept foreigners; thankfully that has also largely been

abandoned. Privatization and new construction has increased competition,

raised standards, and lowered prices. Few hotels meet Western standards,

but then few charge Western prices. I've paid between $1.20 and $12 for

rooms and often get a private bath. Only once did I stay in a dormitory,

and that was in a tiny village. Of the few hotels/guesthouses that refused

me, some were genuinely full, one was run by a cranky official, and one

claimed to lack a police permit for foreigners.

Camping

The Chinese are not into this activity, except for

the nomads of course, but I found carrying a tent worthwhile. I camped four

times in China, three of which were at idyllic spots near a stream.

Cycling

I've been pleasantly surprised just how good

traveling by bicycle is in China. I highly recommend it! My only

previous cycle ride in China was across Tibet from Lhasa to Katmandu,

though I don't really think of Tibet as actually being a part China.

In the afternoon I got together with cyclist Peter Snow Cao, at a teahouse for an

enjoyable afternoon of chatting about cycling. He ran the bicycle tour

company Bike China Adventures for many but has since moved to San

Francisco and a new owner took over the company

http://www.bikechina.com/

A Guaranteed Weight-Loss Program

Looking for a sure-fire plan

to lose weight, while eating whatever you like? Well, all you need to do

is grab your bicycle and head over to the Himalaya! A high-altitude bicycle

ride will melt those pounds and kilograms away. I'm on my last notch of

my belt and my pants fit like a circus tent.

|