India Backpacking 2017-18

Jaipur

24 Oct. Jaipur

Security forces in Bangkok have been in high gear to look after

the huge crowds expected for the late king’s cremation two days from now. So it’s

probably best for me to head out today. I arrived early at Bangkok’s old airport,

Don Mueang, and hung out at the relatively quiet observation room until check-in.

Air Asia’s Flight FD130 on an A320-200 headed into the night sky a little after

8 p.m. for the four-hour flight to Jaipur. It seemed a bargain at $99.26 including

checked luggage even though seating is a bit tight on knee room and no free meals

or entertainment screens are provided.

Jaipur is the capital of India’s

western state Rajasthan, a vast land of deserts and mountains with lots of wonderful

palaces, forts, temples, and stories of chivalry. I cycled extensively in Rajasthan

on my first visit to India in 1984 and again in 2001

www.arizonahandbook.com/India_W2.htm

when I took in the huge camel fair and festival at the sacred lakeside town of Pushkar—camels

to the horizon in every direction! I also made shorter visits in 1993 (backpacking)

mainly to see the bird sanctuary at Bharatpur and in 2010 (cycling)

www.crazyguyonabike.com/doc/AsianJourney

to see the fantastic Jain temples and other sights atop Mount Abu. Jaipur is an

unlikely entry point for India, but the air fare was a deal and the city makes a

good starting point for this trip. I’ve made plans to journey east to Kolkata and

visit many monuments and sacred spots on the way. I’m backpacking now as this route

wouldn’t be good on a bicycle.

My flight turned out to be the only

one to arrive in Jaipur this late at night, so getting through immigration was quick

and easy. A temperamental ATM eventually coughed up 10,000 rupees, the maximum.

Then I bought a 450-rupee pre-paid taxi ticket to Hotel Chitrakatha “A Story per

Stay” www.chitrakatha.co.in/ but on

arrival the person at the desk couldn’t find the reservation that I had made with

hotels.com. He summoned the manager who eventually found the reservation that had

come from Expedia, not hotels.com, hence the confusion. At $30.93 for three nights

I got a modest little single room with hot water and fan. It’s a good place in a

quiet location, and I recommend it.

25 Oct. Jaipur

I had a leisurely

breakfast on the hotel’s rooftop restaurant, then got an autorickshaw (3-wheeler)

through thick and ferociously honking traffic to the City Palace, which stands in

pink majesty in the center of the pink-walled old city. The elaborate Mubarak Mahal

(Welcome Palace) holds a textile museum with incredibly finely woven and embroidered

robes of the maharajas along with saris, shawls, and carpets. Similarly fine metalwork

fills the Armoury, full of swords and blunderbusses. Ceremonial knives with jade

or crystal handles were very popular in the old days! The next courtyard centered

on the open-sided Diwan-i-Khas (Hall of Private Audiences) where the maharajas conferred

with their ministers. Here I turned north into the inner courtyard, Pritam Niwas Chowk,

famed for its four painted gates that correspond to the seasons. The white Chandra

Mahal, residence of royal descendants and only open on very expensive tours, towers

above. Next I had a look at a lineup of old royal carriages, then swung through

the Diwan-i-Am (Hall of Public Audiences) with its portraits of Indian and British

nobility. Across the road I explored the finely crafted astronomical instruments

of Jantar Mantar, begun by Maharaja Jai Singh in 1828. Signs explain how observations

could be made from each of the sculpture-like structures.

Rajendra Pol (gate),

flanked by a pair of marble elephants

Wonderful carved-stone

details abound.

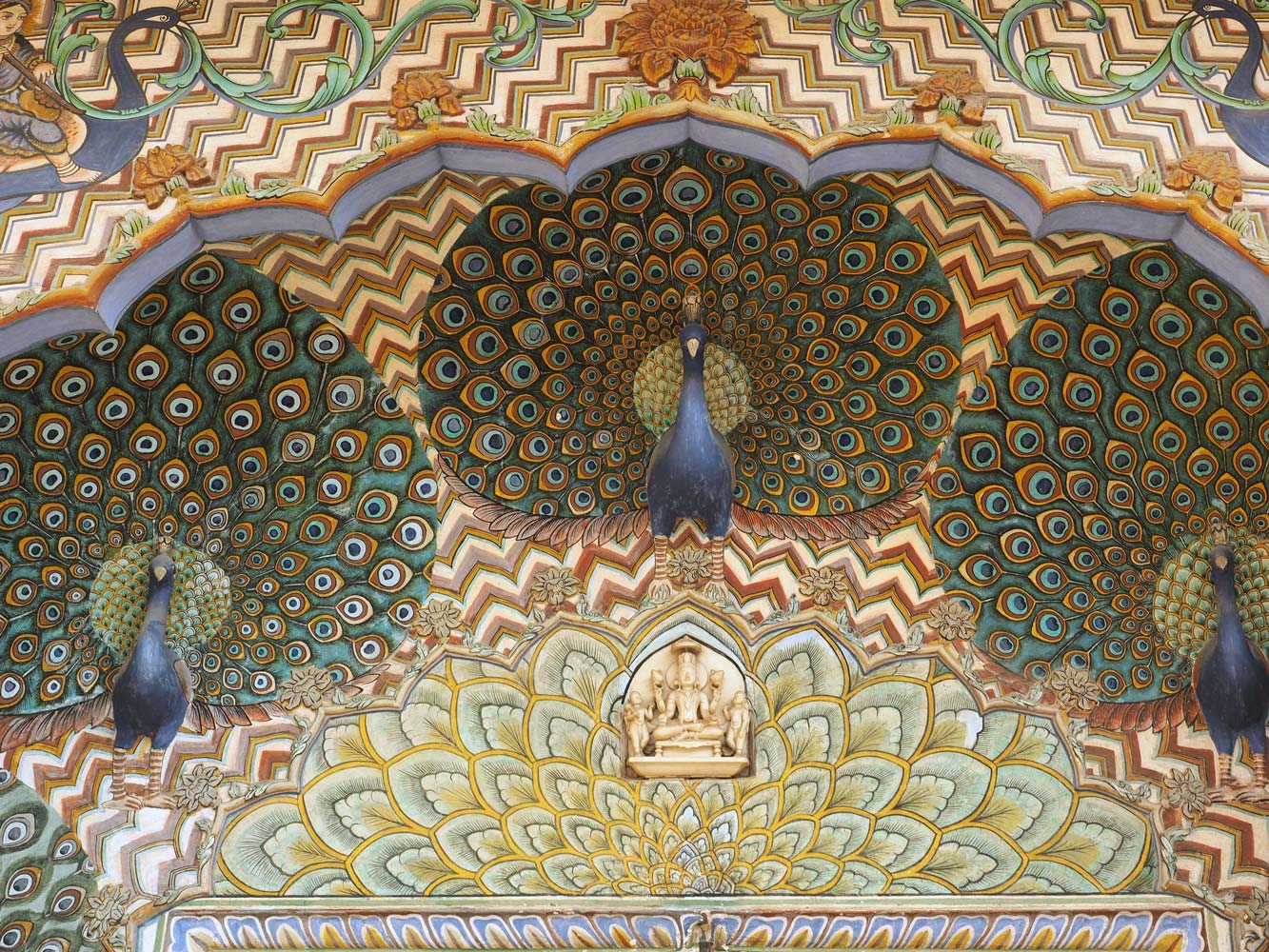

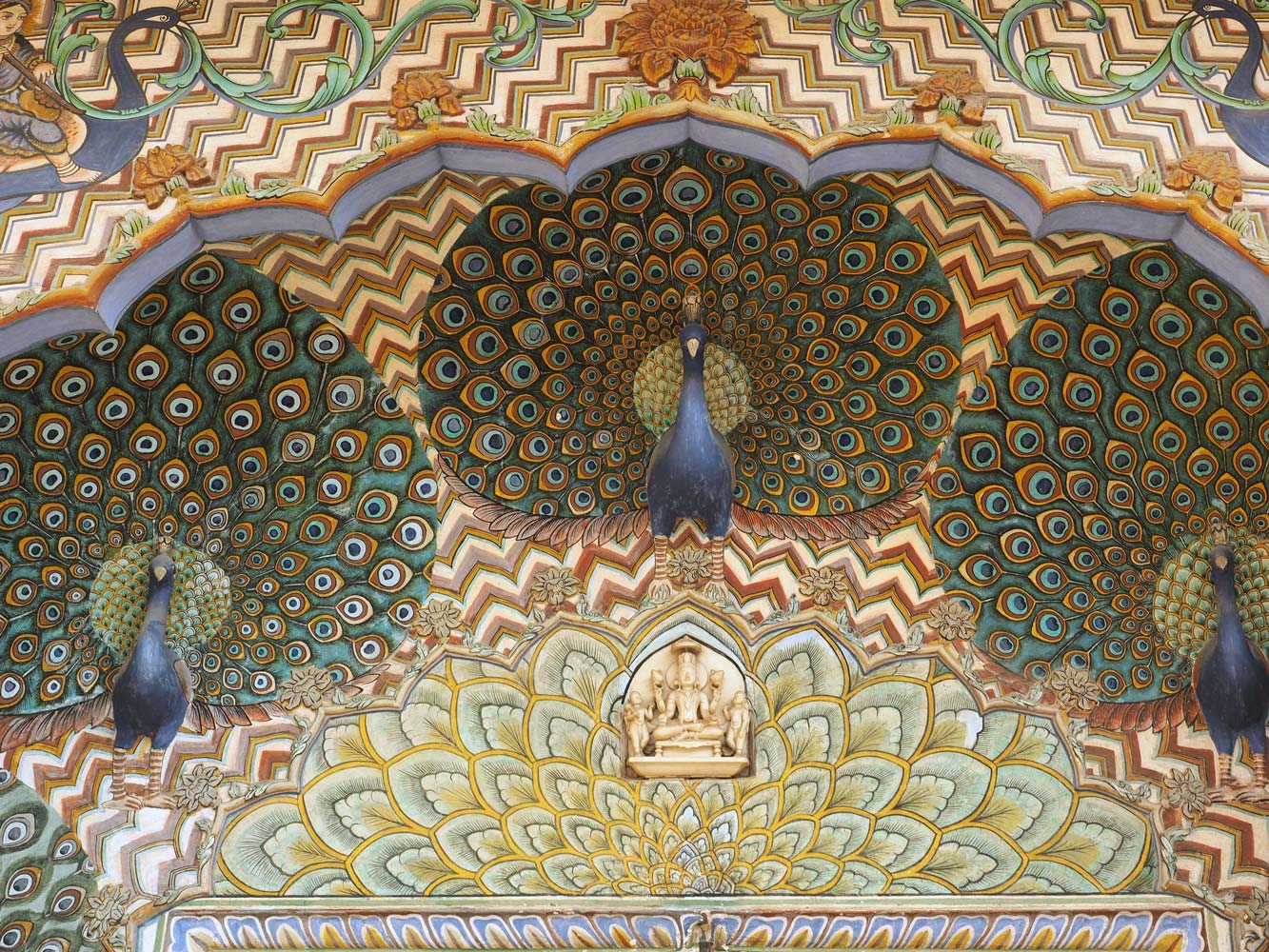

The Peacock Gate (detail) of Pritam Niwas Chowk represents autumn and is dedicated

Lord Vishnu.

There’s a carriage for every occasion.

Vrihat Samrat Yantra

at 90 feet tall is the largest instrument of Jantar Mantar.

You can see the pink

Hawa Mahal in the distance on the right.

Jaya Prakash Yantra

Astronomers used these two half celestial spheres to determine the location of heavenly

bodies.

Rajasthani people turn out lots of colorful paintings, textiles, puppets, and

other creations. There’s a huge shop in the City Palace and I got many an entreaty

to come inside as I walked along Siredeori Bazaar. When I cycled through Jaipur

in 1984, relatively few people owned motorcars, making it a far more pleasant place.

Now traffic barely moves at commute times. I walked a little ways, then took a cycle

rickshaw to Nataraj, a vegetarian restaurant recommended in the Lonely Planet guidebook.

The silver-haired rickshaw wallah was probably older than me, but he managed to

negotiate the traffic safely. Only a small number of cycle rickshaws still operate

in the city and I imagine that when his generation is gone there will be none to

replace it. The use of bicycles also has declined now that almost everyone feels

the need for a motorbike if they cannot afford a car. The Natraj happened to be

closed today, but I found nearby Surya Mahal and got a very tasty and rich North

Indian vegetarian thali along with a fresh-lime soda and bottle of water—I had gotten

very thirsty as well as hungry from the sightseeing.

26 Oct. Jaipur

With an earlier start, I had a porridge breakfast, then hired

an autorickshaw for the day (600 rupees). We first went to Central Museum—a collection

seemingly frozen in time from the late 19th century—in the flamboyant Albert Hall

south of the old city. It’s full of arts and crafts from India, other parts of Asia,

and England. Ceramics and brassware fill much of the lower floor, and there’s a

gallery of carpets including an immense and beautiful ‘Persian garden’ that has

a pictorial design reminiscent of a Mughal garden with trees and flowers divided

by water ways. Upstairs I especially like the superbly detailed miniature paintings

among the textiles and musical instruments.

Back into the heavy traffic,

we maneuvered north to Hawa Mahal, easily Jaipur’s most iconic structure. A maharajah

had the magnificent five-story pink honeycomb facade built in 1799 so that ladies

of the court could discretely watch processions and city life through small openings.

Colored glass adds beauty to the interior. Multiple courtyards provided areas for

the women to stroll outdoors yet out of sight. The heights also offer good views

west to Jantar Mantar and City Palace, north to hilltop Nahargarh Fort, and east

to Siredeori Bazaar and beyond. On the way out I happened upon a gallery of ancient

stone carvings that depict musicians and dancers.

These discreet windows of Hawa Mahal face the inner courtyards.

Delightful viewpoints in Hawa Mahal

Inner courtyards, with a view of Vrihat Samrat Yantra at Jantar Mantar in the distance

Snarling traffic encircles the beautiful old buildings of central Jaipur. (View

from Hawa Mahal)

A shaivoit (follower of Shiva) conversing with another saint holding book, from

a 10th-century music and dance panel

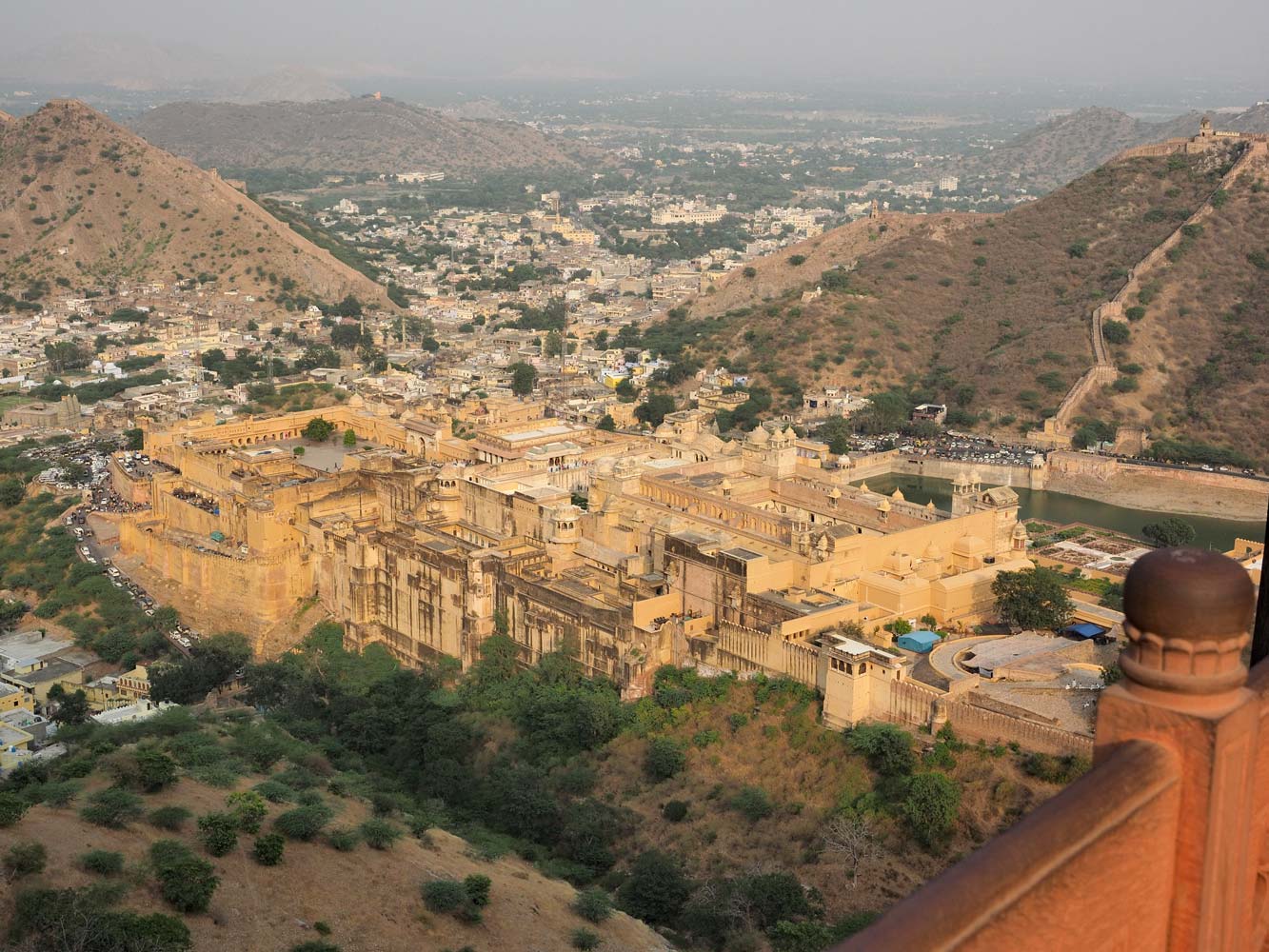

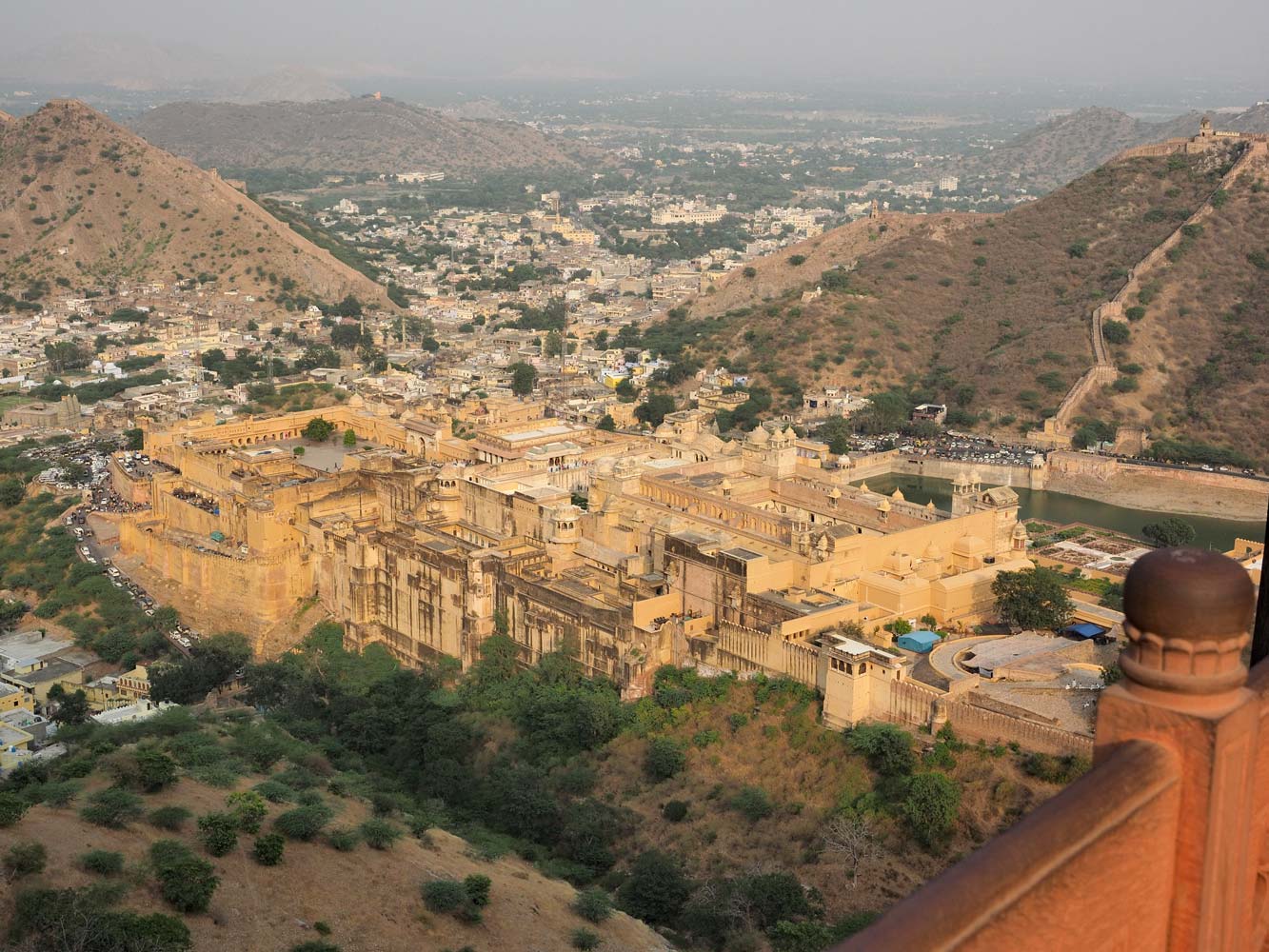

A drive about 13 kilometers northeast climbed into a countryside of rocky hills

to the entrance of Amber Fort, begun in 1592 and easily the grandest palace complex

in the Jaipur area. Oddly the name has nothing to do with the fort’s pretty pastel

yellow color; rather the fort takes its name from the town of Amber, which honors

the goddess Amba. I hiked past a formal garden, then up a stone-paved road to Suraj

Pol (Sun Gate) and entered Jaleb Chowk, the first of four large courtyards. The

expensive combination ticket I purchased yesterday at Jantar Mantar for 1000 rupees

also included Amber Fort as well as the Central Museum and Hawa Mahal, so I didn’t

have to wait in a ticket line today. A stairway led up to the second

courtyard and Diwan-i-Am (Hall of Public Audience), which had been taken over by

a filming crew. More steps led up to the beautifully painted Ganesh Pol gate and

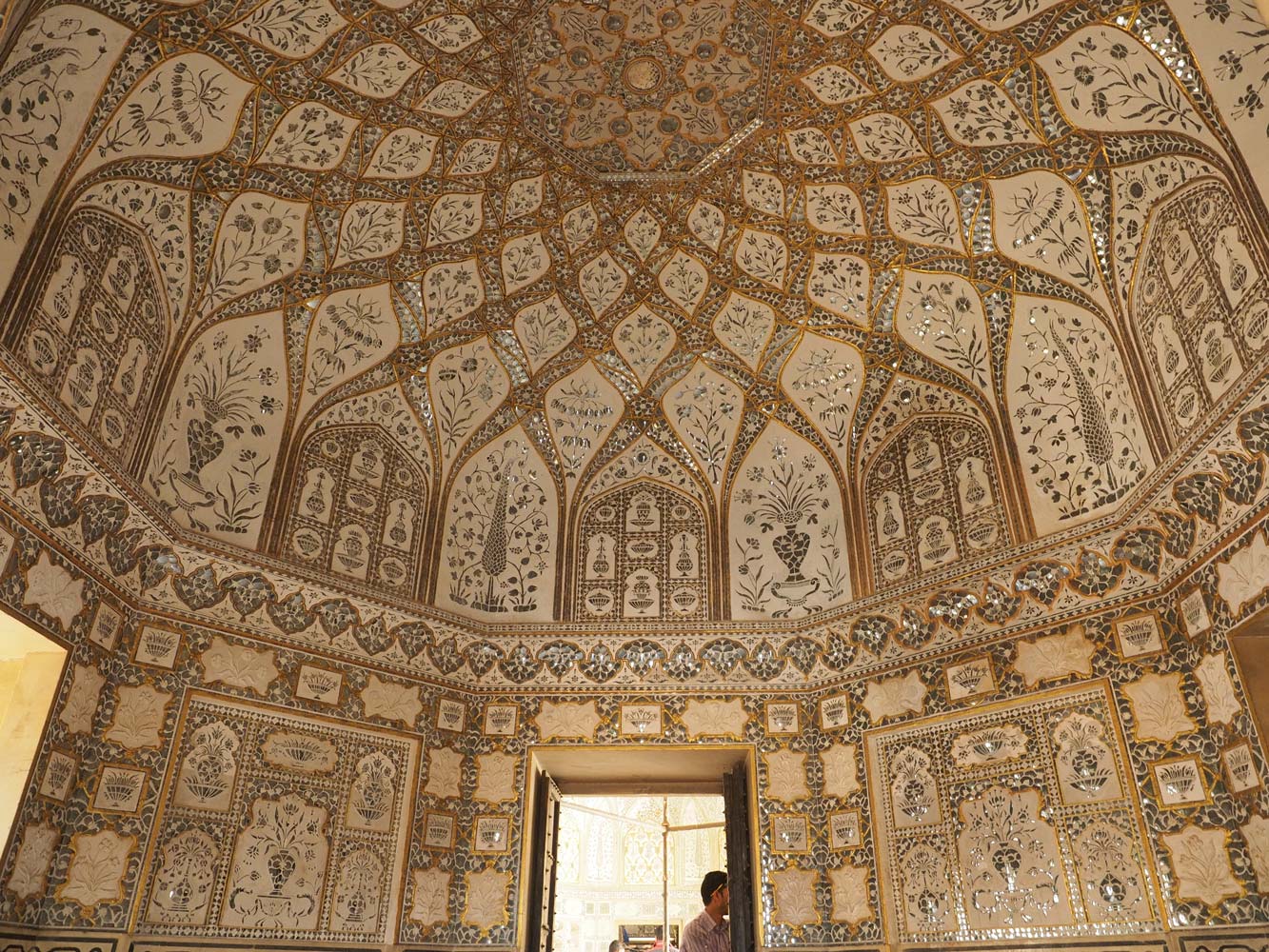

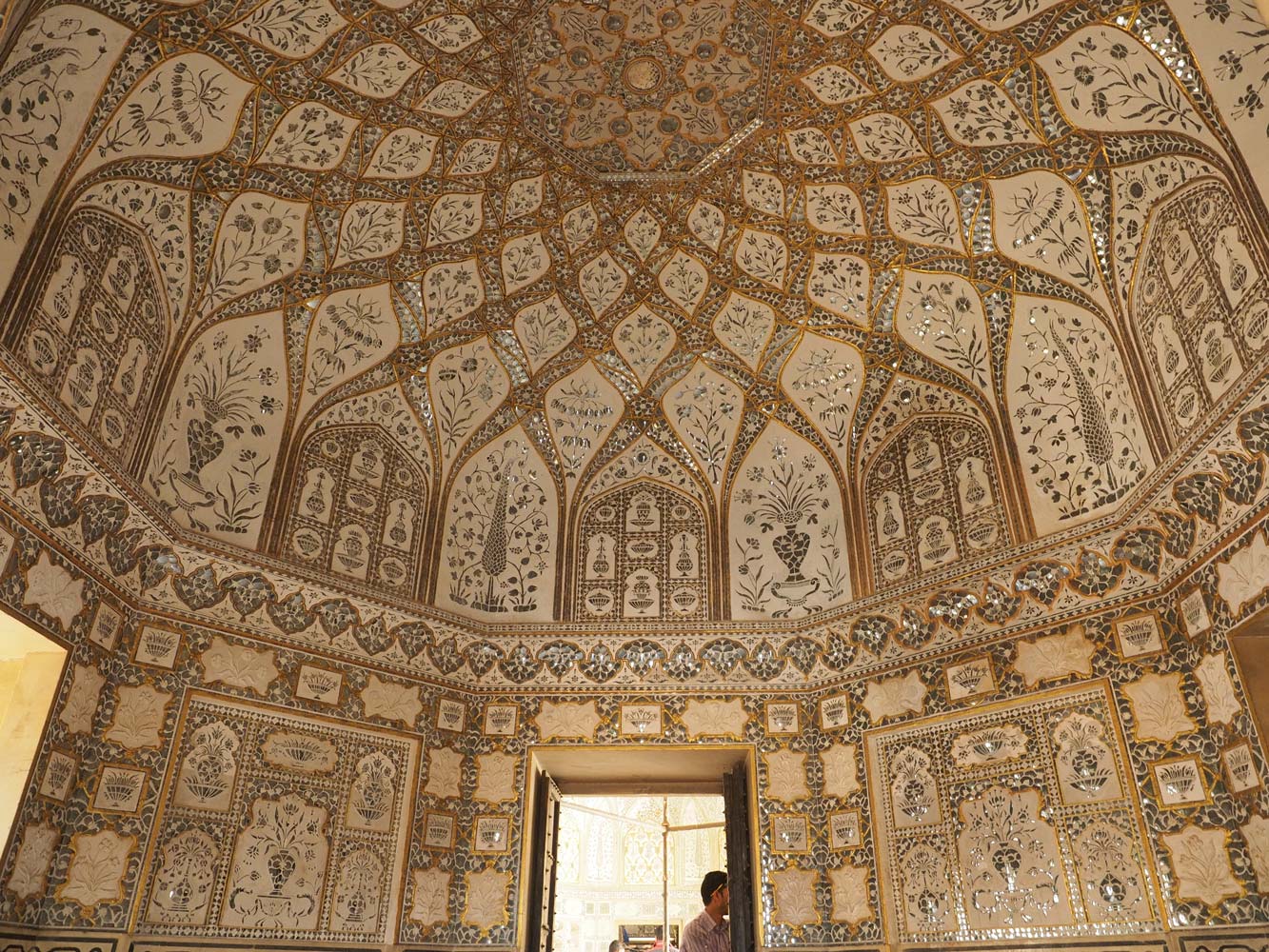

the third courtyard. Here dazzling inlaid mirror work shines in the two-story Jai

Mandir (Victory Hall). On the other side across a formal garden, stands Sukh Niwas

(Hall of Pleasure), which once held a cascading stream—now dry—running across it.

The Zenana, apartments of the maharaja’s many wives and concubines, surround the

fourth courtyard. Passageways and entrances here enabled the maharaja to make nocturnal

visits to his choice of partner without the neighbors being aware. I climbed up

to the heights for great views all around, then descended into the depths of one

of the large water reservoirs, now nearly dry.

The enormous Amber Fort spreads across a ridge.

A formal garden and fountains brings life to the third courtyard in front of Jai Mandir.

Inside the Jai Mandir

A dome of Jai Mandir

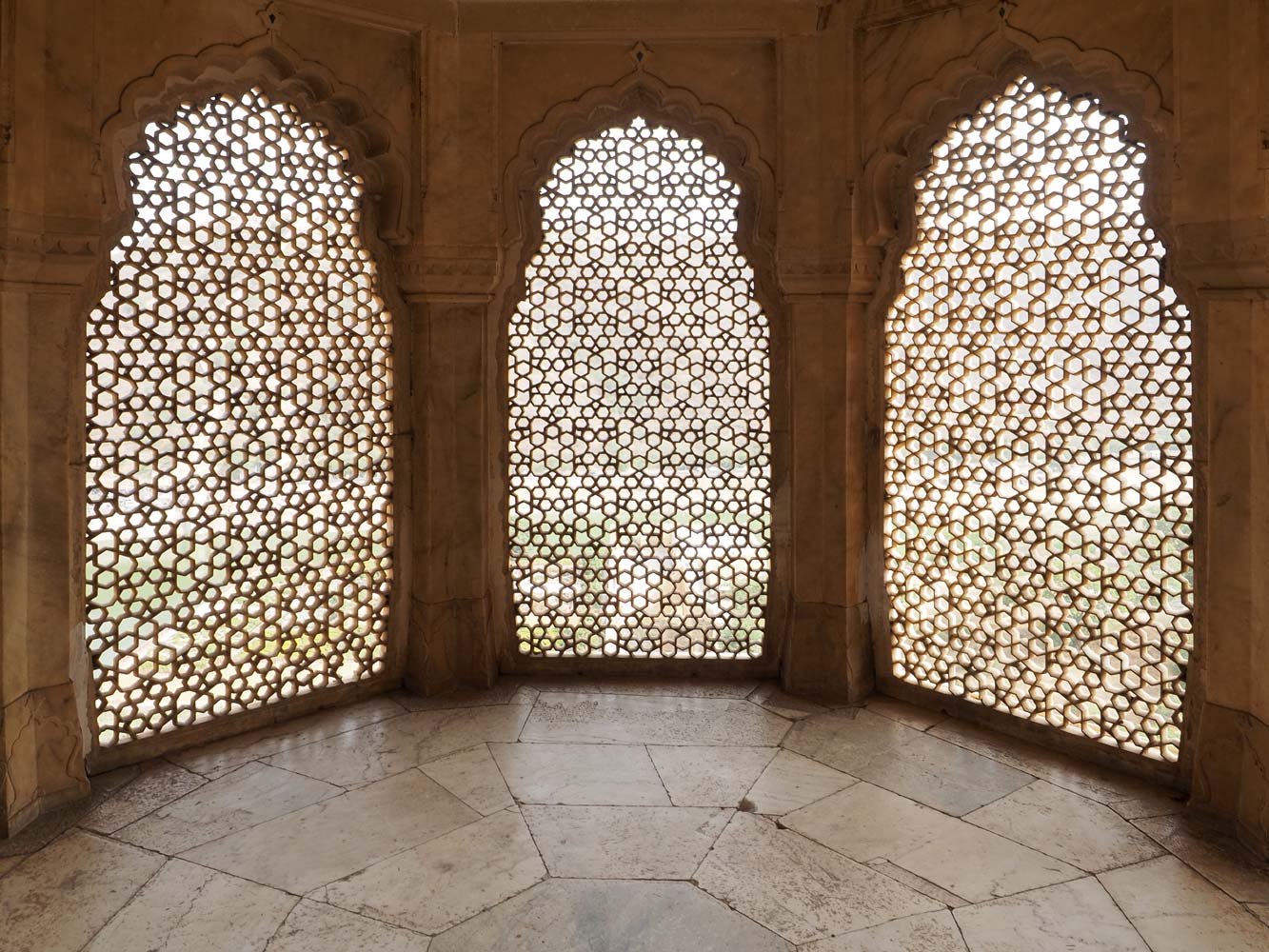

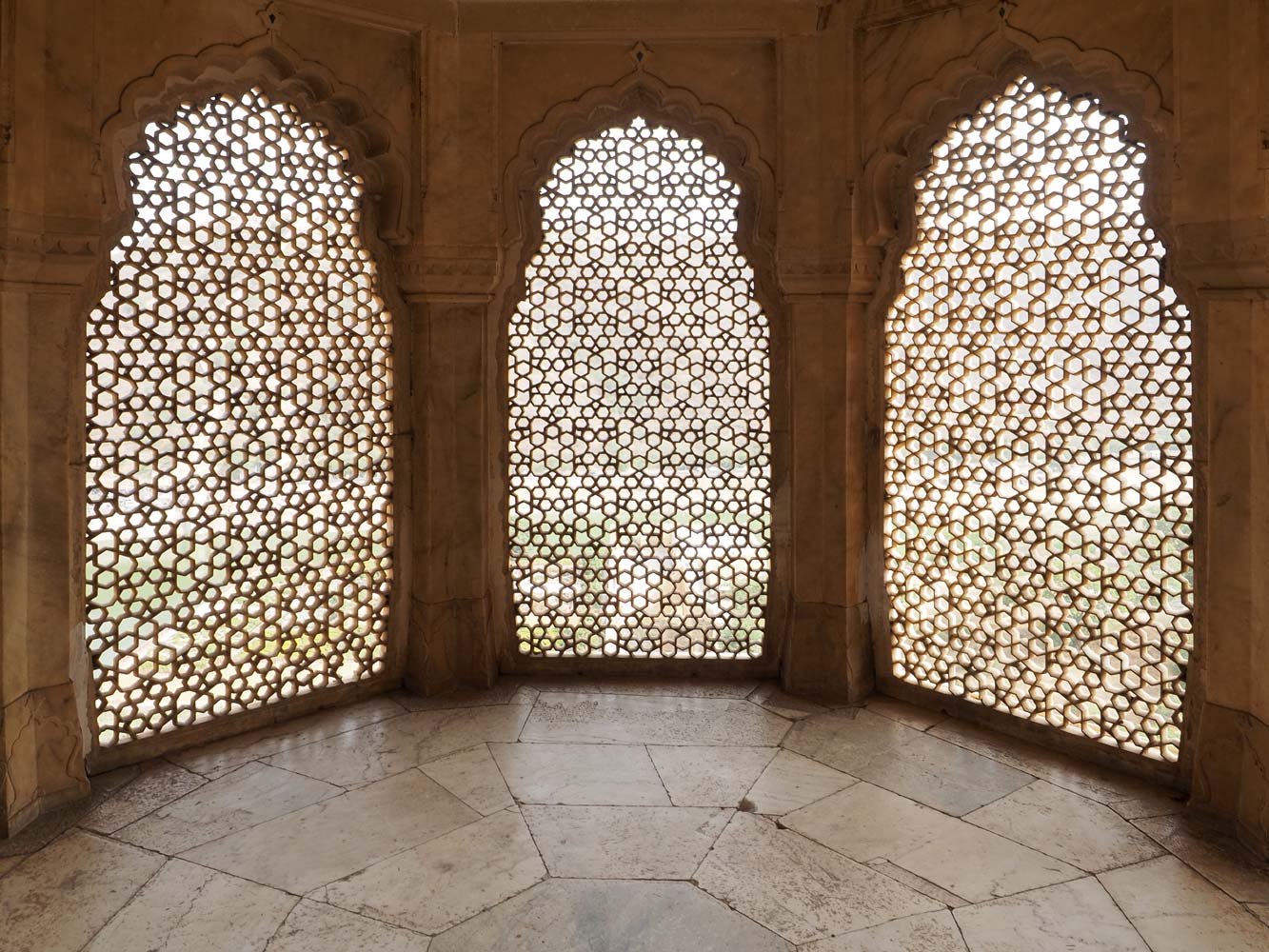

Intricate stone screens of Jai Mandir let in the light while preserving privacy.

A royal toilet

On the way out I happened

to see a sign for a tunnel, said to be a common feature of forts from this period.

The route descended into relative darkness, then inclined upward toward the 1726

hilltop fortress Jaigarh. Farther along the passage way opened to the sky, though

remained hidden in a trench. Steps then led to a gate on the stone-paved road, still

far below Jaigarh. An electric cart offered to shuttle me to the fortress gate for

100 rupees return, and with the afternoon getting late, I hopped on along with several

other tourists. Jaigarh spreads over an immense area on the flat-topped

hill, and the 500-rupee ticket that I purchased yesterday for City Palace also covered

this fort. I first went to a cannon foundry to see old plaster molds and the four-oxen-driven

drill that bored the cannons. Nearby I got a fine view of massive Amber Fort far

below. A guide attached himself to me and led the way through the palace

area, far simpler than those of Amber Fort, but featuring better views. A path led

past royal quarters, then high above a formal garden to a pair of pavilions and

even better panoramas. The guide pointed out two reservoirs below and the path that

camels and elephants trod to bring up water. As we neared the second pavilion, the

guide pulled out his belt and vigorously chased off the langur monkeys, saying they

had a bad habit of jumping onto visitors. Next we passed the dining halls, separate

for men and women, and kitchen areas. Another fellow encouraged me

to visit the giant cannon ‘Jaivana’ at the southern end of the fort complex. Cast

in 1720, the cannon is 20 feet long, weighs 50 tons, and has a range of 22 miles.

It’s probably one of the reasons why invaders never conquered this fort!

A ride down in the electric cart and a long walk past Amber Fort led back to the

main road and my autorickshaw driver. On the way back he stopped at a lakeside park

so I could have a look at the 1799 ‘floating’ Jal Mahal (Water Palace) in the midst

of Man Sagar reservoir.

View from Jaigarh

Plaster molds of the cannon foundry

‘Jaivana’

A courtyard in the heights at Jaigarh

Amber Fort spreads out below Jaigarh.

The ‘floating’ Jal Mahal

The Natraj restaurant on MI Road was open today and I had

a super tasty vegetarian North Indian thali. Jaipur’s weather felt

pleasantly cool at night, warm and sunny by day, completely different from Bangkok

where the monsoon season has lingered with a shower or thunderstorm most days along

with lots of heat and humidity. A perpetual haze lingers in the winter sky, and

I assume that it’s caused by a mix of dust and coal-fired power plant fumes.

27 Oct. Jaipur

A few high clouds drifted overhead, though the chance of rain

stayed at zero. The guesthouse manager arranged a railway ticket through an agent

for the 3.5-hour ride to Agra early tomorrow morning, saving me from having to go

to the station and wait in line. In the afternoon I ventured by autorickshaw

into heavy traffic for a ride into a little rocky valley just north of town to visit

the Royal Gaitor (Gatore ki Chhatryan), cenotaphs of the maharajas. Beautifully

carved stone pavilions of white marble and fine-grained pink or white sandstone—all

very well preserved—honor the deceased rulers. A few structures also have carvings

of musicians and dancers. Nahagarh (Tiger Fort) towers high above and stone walls

course across the hillsides.

Cenotaphs of the Royal Gaitor (Gatore ki Chhatryan) have wonderful stonework.

Back in town, I swung by Surya Mahal, this

time going for South Indian cuisine—a masala dosa and uttapam, followed by a banana

split—all divine! A couple days ago a newspaper had announced the Kaharwa Fusion

band tonight at Jawahar Kala Kendra, an art center in the south of the city, and

I headed there for the free 7 p.m. performance. The 11-member group combined Indian

classical music, Rajasthani folk music, and Western styles and instruments for an

entertaining program of mainly vocals plus instrumental interludes. Afterward I

found an autorickshaw for the ride back to the guesthouse, but this one was electric

and a bit slower than the high-polluting normal machines.

Four of the eleven musicians of the Kaharwa Fusion band

They play classical

Indian instruments like sitar, harmonium, and tabla; folk instruments including

dholak, khartal, morchang, and bhapang; and Western instruments such as

violin, guitar, keyboard, and drums.

On to Agra and the Taj Mahal