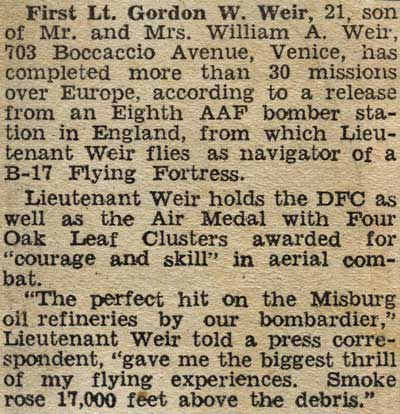

German production of fighter aircraft actually increased through 1944 into 1945. The dispersed manufacturing plants were beyond our power to seriously damage. Therefore, some postwar surveys concluded that our bombing offensive was a failure. But our bombing was just good enough that the Luftwaffe fighters had to keep rising to attack us, and then they were mostly destroyed by our P-51s and P-47s. So the Luftwaffe suffered a shortage of pilots rather than a lack of planes. And thanks to our efforts at such places as Misburg and Merseburg they ran out of aviation fuel even before they ran out of pilots. Thus we gained mastery of the skies, and from D-Day on our troops knew that their enemy was earth-bound.

Heroism

Military heroism is perhaps mostly a matter of getting used to combat as a way of life, to carrying on in a normal way in an abnormal environment. In our B-24s and B-17s we had no way of warding off the shrapnel fired at us. We had to sit there and take it. Some men of the 493rd could not function in combat; they were sent home. What were the limits of our personal endurance? What if all the missions had been like the one to Magdeburg? We could not know our breaking point. And yet, I like to think that our crew if ordered to fly a 50-mission tour, as did many bomber crews in the 15th Air Force out of Italy, we'd have done so with no more than the usual number of expletive-punctuated complaints.

A Lesson Learned

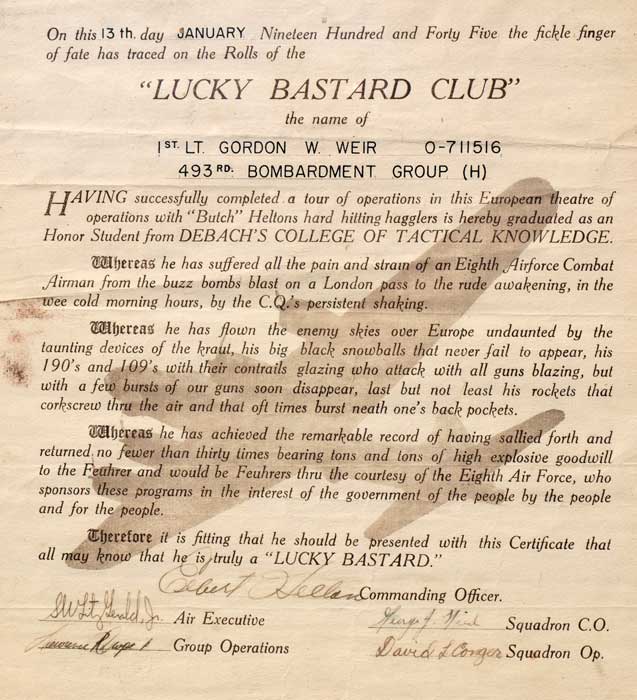

In 1944-45 I didn't indulge in philosophic speculations on the turn in from the IP. As we floated through the flak in our aluminum foxhole, I was trying to climb up into my helmet. Nevertheless, the lesson learned from combat is that there is a lot of luck, chance, and fortune in life. I've been lucky.

|  |

Air Medal (left) and Distinguished Flying Cross (right) My three Battle Stars represent Operation Overlord (Allied invasion of France) and two other campaigns. Each of the four Oak Leaf Clusters represents five missions, so I could have been awarded more of these. |

The War in the Air For a saving grace, we didn't see our dead, Seldom the ghosts came back bearing their tales Who had no graves but only epitaphs That was the good war, the war we won Howard Nemerov |

| Howard Nemerov (1920-1991). Nemerov first joined the Canadian Air Force in World War II and flew combat missions against the Germans. He later served in the United States Army Air Corps from 1943 to 1945. He teaches at Washington University in St. Louis, Missouri. His Collected Poems won the Pulitzer Prize and the National Book Award in 1978. He served as poet laureate of the United States in 1989 and 1990." From Stokesbury, Leon, ed., 1990, Articles of War: A Collection of American Poetry about World War II |

|

Back to Navigating Through World War II Home Page